The horse: A work of art

Breed genetics vs. primal genetics

When back in 1956 in the Olympic Games of Stockholm the German show jumper Hans Günter Winkler and his mare Halla cleared one obstacle after the other with ease and precision the spectators didn't believe their eyes. Winkler had pulled a groin muscle in the first round and therefore was in massive pain and physically severely impaired in the second round. He was nearly unable to give aids and far from being of any assistance to the horse. Nevertheless, the courageous mare carried her rider with great skill and won the gold medal: Olympic champion 1956 – a legend was born!

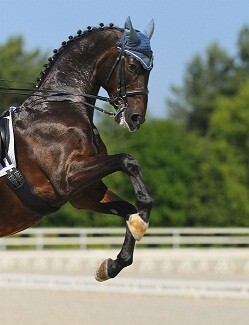

Then and now breeders produce horses of exception with enormous potential. Those horses carry a genetic disposition to achieve outstanding performance – if they are able to tap into their talent. A current example of such a horse of exception has just been retired from sport.

We see them in auctions and young horse classes: highly talented horses that change hands for huge sums. Buyer pay prices as if they would not be dealing with (ephemeral) living crea-tures, but with investments in works of art. Recently, for example, Claude Monet's «Iris Mauves» went under the hammer for 10.8 pounds. This is about the same sum that has been paid for the most expensive dressage horse ever.

But why do most of those youngsters never show up again afterwards? Why do high-quality Grand Prix horses have to be retired from sport at the age of 15, mostly because of health issues? They have an outstanding genetic disposition – but still? Do breeders only produce short-lived works of art without resistance?

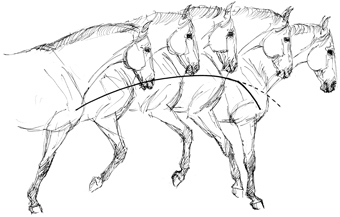

It is important to recognise that early wear occurs when certain genetic factors are not taken into account during training. Because besides the breed genetics (in other words: the pedigree or talent) horses also carry the primal genetics of the flight response. And those primal genetics are in total conflict with the requirements for the modern riding horse. The longer a horse is exposed to the strain of the riding horse, the more the physical consequences of the instinct-based movement pattern of primal genetics predominate and the breed genetics are suppressed. If horses do not learn in training how to cope with primal-genetic factors such as handedness, crookedness or heaviness on the forehand, then they cannot make full use of their talent and potential because of physical discomfort and finally medical problems resulting from unaddressed primal-genetic issues.

This explains why the majority of the starlets of foal auctions and young horse classes never show up again. As long as those youngsters are not ridden or are under saddle since only a short time the impairment due to primal genetics is still weak or does not exist and the talent reveals itself in all its splendour. The longer the training continues, the more pressure the rider applies and the broader the therapeutic entourage becomes to try to cover up supposed weaknesses. Primal genetics are trampled underfoot with tension-induced extravagant gaits. The works of art from the past deteriorate into artificial works of misguided training. And it is only cynical to say that the modern horse of exception distinguishes itself exactly because it is capable to withstand this enormous pressure.

From child prodigy to problem child

So what happens to the highly talented horses that do not withstand the pressure and slip through the net? If they are not retired at the age of 15 and condemned to spend the "eve of their lives" on the pasture behind the indoor arena, they are sold. Promising pedigree becomes now affordable for the ambitious hobby rider. The fascination for the horse as a work of art makes them blind for physical deficiencies and the family tree raises high expectations. Only a short time later disillusionment ensues: under the saddle of the average rider shortcomings in training come to light sooner or later. Gait impurities, disobedience, tension, blockades and poor rideability lead the desperate horse owner into the spiral of medical treatment. This is very costly and arduous. And it is often observed that the dream of owning a real crack turns into a nightmare.

Now the hobby rider has to make up for all omissions of the past. His or her insatiable will to understand nourishes the market with an almost unmanageable variety of clinics, books, DVDs, feed supplements and alternative medicines. There is a wide range of possibilities and the demand does not decline. Most of the clients who bring their horses to the ARR Center of Anatomically Correct Horsemanship have a long – and costly – history of suffering behind them. The sobering revelation can sometimes be cruel that after only a few weeks of training according to the ARR principles the «incurable» horse finds rhythm and suppleness, reveals unimagined motivation and riding with discrete aids in lightness becomes simply a logical concomitant. Because only the question whether or not we take the primal genetics into account during training and during everyday riding determines success or failure.

Good muscles, bad muscles

We meet horses that have developed massive compensatory muscles because of wrong training methods. However, those muscles are dangerous because they favour skeletal shifts, alterations in facet joints, bone oedema or arthritic changes. They are intended for the sole purpose of satisfying the owner who is happy to see that the horse changes and develops muscles. Nevertheless, those muscles inhibit movement and impede the breed-genetic disposition to unfold – the talent remains untapped. On the other hand, if the primal genetics are addressed with gymnastic training even skeletal weaknesses or other signs of wear can be rehabilitated.

Talisman – to name but one – is such a horse. The grey stallion with excellent pedigree was born in Denmark in 1995. From an early age this son of Weltmeyer was a great mover and showed enormous willingness to work. He was reserve champion at the stallion licencing and as the undisputed winner of the Danish championships, he qualified for the world championships for young dressage horses. The impressive stallion became the darling of the public and still today people remember him vividly.

Already at the age of 6 various injuries slowed down his sports career. He stood at stud with great demand in Denmark and later in Norway. His entourage, veterinarians and physiotherapists took good care of him, but he did not get back in shape as before. When a Norwegian para dressage rider trained him with the aim of participating at the Paralympics 2012, he was lame repeatedly as he went through the exercises. However, no veterinarian was able to explain or cure it. When there was less and less interest from breeders, two young hobby riders bought Talisman at the age of 17 and brought him to us for training. Back then, he was both physically and mentally in poor condition. We documented his development in a training journal and today the sprightly senior shines in a new light. It is never too late to teach a horse to cope with primal genetics.

The shortcomings in Talisman's education were most striking when the physically impaired para dressage rider rode him. What seemed to be perfection when a strong rider presented him with tense gaits and in a very short frame, could not be reproduced without this massive force. Inevitably, the unaddressed primal-genetic weaknesses resulted in gait impurities. Conversely, Halla at the Olympics in Stockholm was able to carry herself and her physically impaired rider with no fault through a most challenging course thanks to the thorough training she had enjoyed – and she was 34 years old when she died.